Keywords: sixth mass extinction, biodiversity loss, human-driven extinction, species decline, climate change, ecosystem collapse, extinction threshold, conservation science

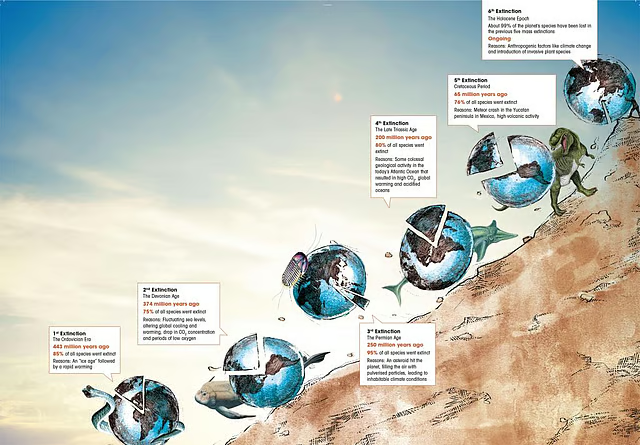

Introduction: What Is a Mass Extinction?

A mass extinction event refers to a relatively short geological period during which at least 75% of species go extinct across a wide range of habitats and taxonomic groups. Earth has experienced five mass extinctions over the last 540 million years, the most famous being the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Now, many scientists argue that we may be entering—or already living through—a sixth mass extinction. But new research challenges this claim, stating that current extinction patterns, though deeply alarming, may not yet meet the extreme thresholds that define a true mass extinction.

So—are we really facing a sixth mass extinction, or are we prematurely ringing the alarm bells?

The Current State of Biodiversity

Human activities have profoundly altered Earth’s ecosystems. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES):

- Over 1 million species are currently at risk of extinction.

- Biodiversity is declining faster than at any other time in human history.

- Wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69% since 1970, according to WWF’s 2022 Living Planet Report.

This collapse isn’t limited to charismatic megafauna like elephants or tigers. Entire classes—insects, amphibians, corals, and birds—are declining at alarming rates.

Causes of modern biodiversity loss include:

- Habitat destruction

- Climate change

- Pollution

- Overexploitation

- Invasive species

Yet, whether this constitutes a “mass extinction” in a geological sense remains under debate.

The New Study: Not Quite a Mass Extinction (Yet)

A 2024 study published in PLOS Biology, led by ecologist Peter Wagner, analyzed extinction rates across over 22,000 genera—not species. Their reasoning: past mass extinctions are defined by higher taxonomic losses, not just species disappearances.

Key Findings:

- Less than 2% of mammal genera have gone extinct in the past 500 years.

- Across all groups studied, only about 0.5% of genera have disappeared.

- Current extinction rates are elevated but not yet catastrophic on a geologic scale.

Interpretation:

These figures suggest that we’re not technically experiencing a mass extinction by paleontological standards—yet. However, researchers caution that we may be on the brink, especially if current trends continue.

Why Scientists Are Divided

The concept of a sixth mass extinction is scientifically controversial, in part due to:

1. Definitions and Thresholds

Mass extinctions are defined based on genera-level loss across multiple ecosystems. But public and media attention often focuses on species-level extinctions, particularly of large, well-known animals.

2. Time Scales

Most past extinctions unfolded over thousands to millions of years, while the current biodiversity crisis has escalated rapidly within a few centuries—or even decades.

3. Population Decline vs. Extinction

Ecologist Paul Ehrlich and conservation biologist Gerardo Ceballos argue that population collapses are just as ecologically damaging as outright extinctions. The disappearance of local populations weakens ecosystems long before species are formally extinct.

“You don’t need to wait until 75% of species are gone to have a catastrophe,” says Ceballos. “Collapse happens much earlier.”

Climate Change: The Accelerating Threat

Even if current extinction rates aren’t high enough to be labeled a mass extinction, climate change could soon tip the balance.

According to projections:

- 30% to 50% of all species could be at risk of extinction by 2100 if global temperatures rise by 2–3°C.

- Coral reefs, polar species, amphibians, and tropical plants are especially vulnerable.

- Sudden climate tipping points (e.g., permafrost thaw, Amazon dieback) could trigger cascading ecosystem failures.

It’s Not Just About Species – It’s About Ecosystem Collapse

Insects—particularly pollinators like bees and butterflies—are vanishing at alarming rates. Their disappearance threatens global food security, as nearly 75% of crops depend on pollination.

Meanwhile, amphibians are undergoing what may be the worst extinction crisis of any vertebrate group—due to disease (chytrid fungus), pollution, and climate change.

When keystone species vanish, entire ecosystems unravel.

Are We at a “Point of No Return”?

According to a 2024 WWF report, we may be approaching multiple ecological tipping points—thresholds beyond which ecosystems cannot recover:

- Tropical forests turning to savannas

- Melting permafrost releasing methane

- Ocean acidification disrupting marine life

Once these tipping points are passed, even halting human activity may not restore lost biodiversity.

What Can Be Done?

✔ Strengthen Global Conservation Policies

- Expand protected areas and enforce conservation laws.

- Combat illegal wildlife trade and deforestation.

- Support community-led conservation in biodiversity hotspots.

✔ Curb Climate Change

- Cut carbon emissions in line with Paris Agreement targets.

- Transition to renewable energy.

- Invest in nature-based climate solutions (e.g., reforestation, wetland restoration).

✔ Rethink Consumption

- Promote sustainable agriculture and fishing.

- Reduce meat consumption and food waste.

- Support ethical, eco-conscious brands.

Final Thoughts: A Sixth Mass Extinction—Not Inevitable, But Possible

Whether or not Earth is technically in a sixth mass extinction, one fact is clear: biodiversity is declining rapidly, and human activity is the main driver.

The real danger lies in complacency. Framing the issue as “not yet a mass extinction” risks minimizing the urgency of the crisis. Instead, it should motivate action—because we still have time to reverse the trend.

Every species we save, every forest we protect, and every action we take toward sustainability delays the tipping point. The sixth mass extinction may not be a certainty, but it’s a possibility we can still prevent.

Leave a Reply